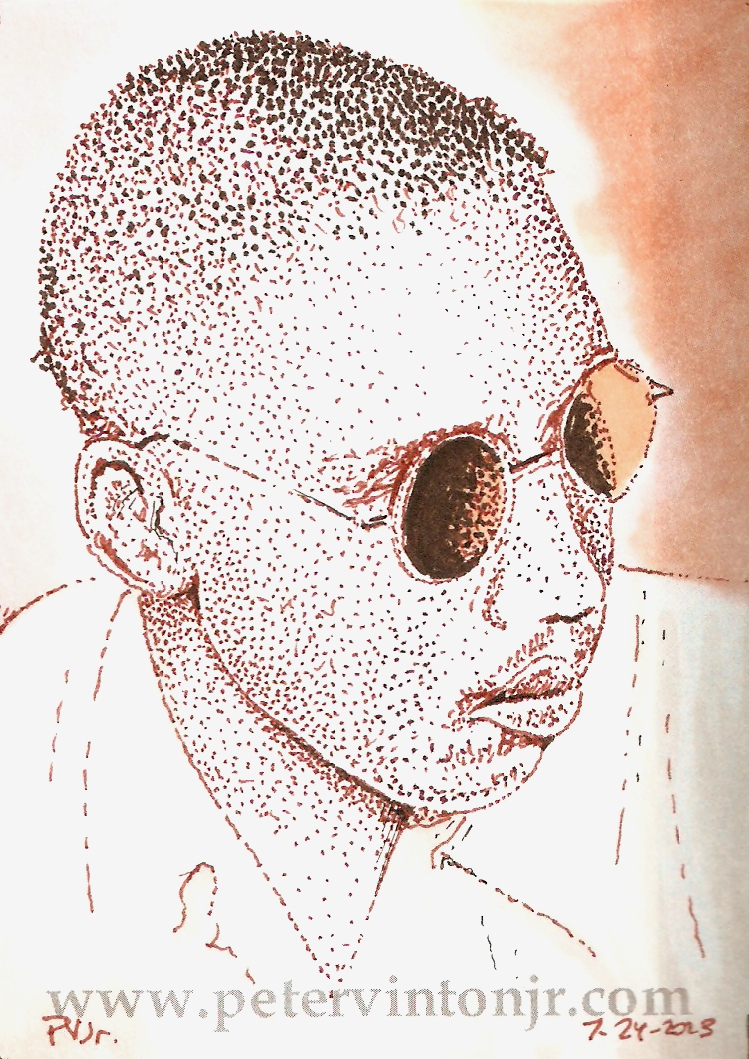

An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted 7/24/2023

Prelude | 128 | 129 | 130 | 131 | 132 | 133 | 134 | 135 | 136 | Email |

|---|

Born in 1919 South Carolina into a family of sharecroppers, WWII veteran Isaac Woodard knew struggle and poverty from a very early age --dropping out of school at the age of 11 and then leaving home altogether at 15, in search of better prospects than Fairfield County. After some years laboring in a lumberyard, Woodard joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal public work relief program. In 1942, Woodard was drafted into the U.S. Army, along with an estimated 675,000 other Black Americans. He was eventually deployed to the South Pacific in 1944, serving with the 429th Port Battalion --a segregated unit. During the brutal New Guinea campaign, Woodard saw a great deal of action and was promoted to Corporal, and then ultimately to Sergeant, earning a battle star for combat service, along with a number of other medals. Thusly decorated, Woodard was honorably discharged from service and flew home to Augusta, Georgia, where on February 12, 1946, he caught a bus back to South Carolina and his family --literally the very last leg of his long journey home.

Enroute, a stray comment from Woodard to the bus driver about rest stops swiftly led to an altercation --the bus driver deemed Woodard's "attitude" to be insufficiently deferential, resulting in a call to the Batesburg-Leeville, South Carolina police department. In very short order Woodard found himself arrested and severely beaten by police, gouging out both of his eyes. Still in his uniform, Woodard was left sightless overnight in a jail cell, only to be formally charged with "drunk and disorderly conduct" the following morning. Woodard spent the next 2 months in a VA hospital, ultimately rejoining his family in New York, where they had decided to move.

Unprepared for a life of blindness in an unfamiliar city, Woodard reached out to the NAACP, who took up his case and turned him into something of a cause célèbre for a time --even meriting publicity from such luminaries as actor Orson Welles, and musicians Nat King Cole and Billie Holiday. Woodard found himself crisscrossing the very nation he had served, recounting his story and garnering some measure of fame, though this would be of no practical help during two failed attempts to bring his attackers to trial. The ultimate measure of Woodard's notoriety came in 1948 when President Truman issued Executive Order 9981, desegregating the U.S. Armed Forces (see Lesson #68 in this series).

Woodard's time in the national spotlight soon faded and he was faced with the more immediate problem of obtaining benefits from the VA --on a technicality, since his assault and blinding happened after his term of service, he did not qualify for full benefits nor payments. Woodard was forced into public housing in the Bronx but with his family's help was ultimately able to buy the building and became a landlord, living quietly and mostly forgotten for the next decade. In 1956 an article in Jet magazine brought some measure of national attention back to his plight and eventually led Congress to pass an amended piece of legislation that would now award full disability benefits to any veteran injured between their time of discharge and their arrival at home. Further legislative improvements to VA benefits followed in the 1970s, and Woodard was able to purchase additional property in the Bronx and lived there with his sons until his death in 1992. He is buried with other U.S. veterans at Calverton National Cemetery and a plaque now marks the site in Batesburg-Leeville where Woodard was attacked and dragged from his bus.

Next page - Lesson 133: June Elizabeth Johnson