Lesson 147:

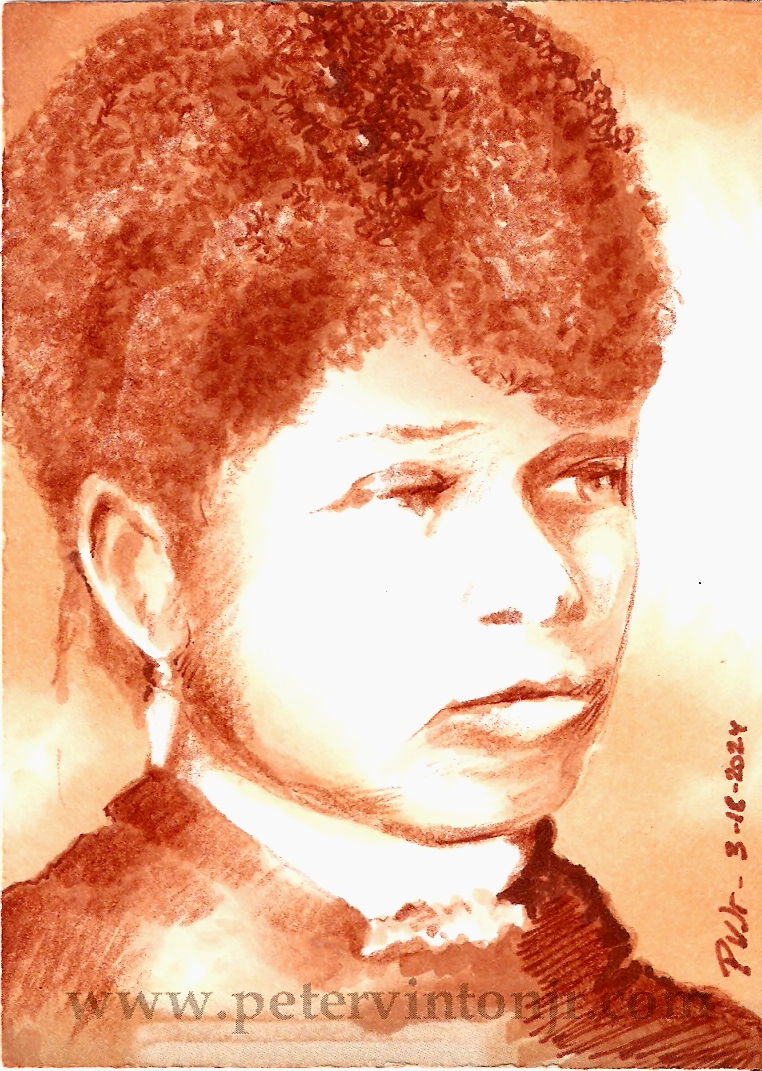

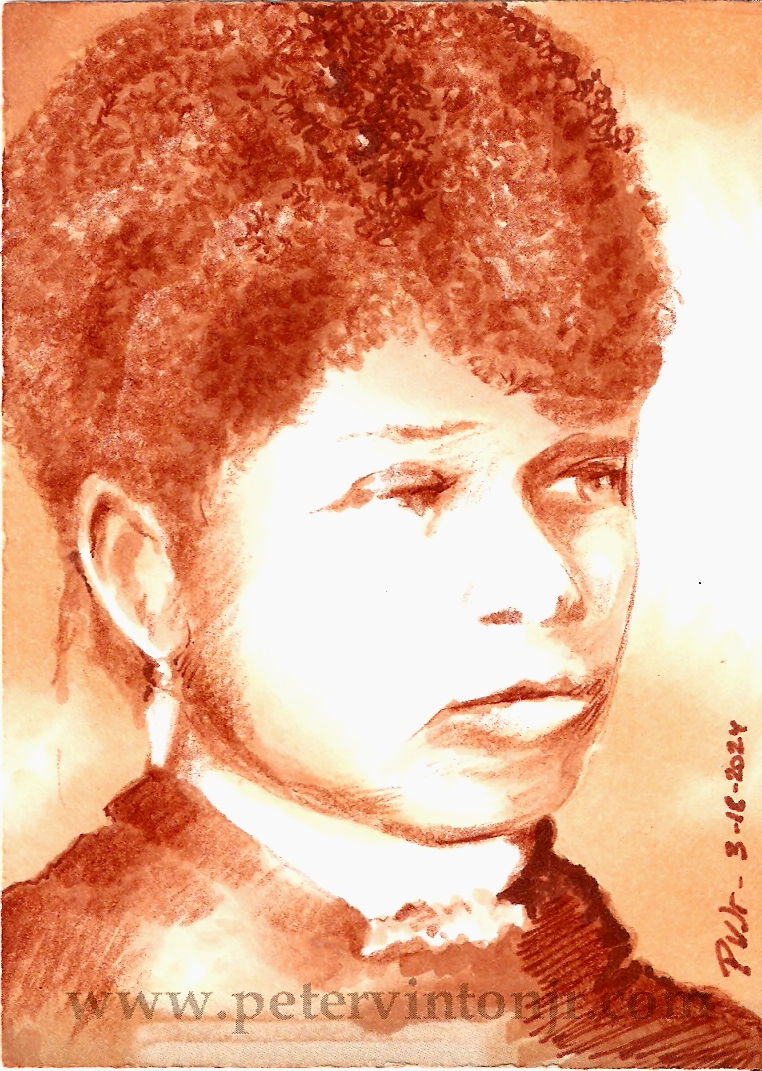

Sarah Boone

An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted 3/18/2024

Continuing with some amazing women's biographies this month, today we look at the life of Sarah Boone. While details of her early life are scant, it is at least known that she was originally born to enslaved parents in 1832 North Carolina, and later married a free Black man, James Boone, in 1847. At some point before the Civil War, the couple and their 8 children --along with Sarah's own mother-- made their way to Connecticut by way of the Underground Railroad.

Continuing with some amazing women's biographies this month, today we look at the life of Sarah Boone. While details of her early life are scant, it is at least known that she was originally born to enslaved parents in 1832 North Carolina, and later married a free Black man, James Boone, in 1847. At some point before the Civil War, the couple and their 8 children --along with Sarah's own mother-- made their way to Connecticut by way of the Underground Railroad.

The Boones settled in New Haven and took jobs; James as a bricklayer and Sarah as a dressmaker --successfully earning enough to be able to buy and own their own house, which was an unusual achievement for a Black couple at the time, even in New England. The Boones became members of the Dixwell Congregational Church and it is assumed that, through this association, Sarah learned to read and write. Sarah's skill as a dressmaker eventually blossomed into full-on business ownership, and at one point she considered the question of how to iron corsets with their curved, tight-fitting contours. Through trial and error Sarah improvised a narrower, curved plank that could slip into sleeves, and would allow for greater freedom of movement with the iron, without producing as many wrinkles or creases. Over time she added padding to the plank to reduce impressions from the iron, and also came up with a method to collapse this curved plank on a hinged platform, for easier storage.

The Boones settled in New Haven and took jobs; James as a bricklayer and Sarah as a dressmaker --successfully earning enough to be able to buy and own their own house, which was an unusual achievement for a Black couple at the time, even in New England. The Boones became members of the Dixwell Congregational Church and it is assumed that, through this association, Sarah learned to read and write. Sarah's skill as a dressmaker eventually blossomed into full-on business ownership, and at one point she considered the question of how to iron corsets with their curved, tight-fitting contours. Through trial and error Sarah improvised a narrower, curved plank that could slip into sleeves, and would allow for greater freedom of movement with the iron, without producing as many wrinkles or creases. Over time she added padding to the plank to reduce impressions from the iron, and also came up with a method to collapse this curved plank on a hinged platform, for easier storage.

In other words: Sarah invented the modern-day ironing board.

In 1891 Sarah applied for, and received, U.S. Patent #473,653 --making her one of the first* Black women inventors to earn a patent:

Sarah remained in New Haven for the rest of her days and died in 1904. Surviving business records would seem to indicate that Sarah received little in the way of monetary gain, from the mass-commercialization of her invention; nevertheless her work stands as an important prototype, for an ordinary household object that is so familiar and so universal, that it is difficult to imagine a time before it existed.

( * - While details are conflicting, the VERY first Black woman inventor to receive a U.S. patent is popularly assumed to be Judy W. Reed, inventor of an improved dough kneader and roller in 1884 --however Reed's patent application and its associated documents reveal almost nothing about her life or circumstances.)

Next page - Lesson 148: Alice Augusta Ball

Return to www.petervintonjr.com Main Page

Continuing with some amazing women's biographies this month, today we look at the life of Sarah Boone. While details of her early life are scant, it is at least known that she was originally born to enslaved parents in 1832 North Carolina, and later married a free Black man, James Boone, in 1847. At some point before the Civil War, the couple and their 8 children --along with Sarah's own mother-- made their way to Connecticut by way of the Underground Railroad.

Continuing with some amazing women's biographies this month, today we look at the life of Sarah Boone. While details of her early life are scant, it is at least known that she was originally born to enslaved parents in 1832 North Carolina, and later married a free Black man, James Boone, in 1847. At some point before the Civil War, the couple and their 8 children --along with Sarah's own mother-- made their way to Connecticut by way of the Underground Railroad.