Lesson 201:

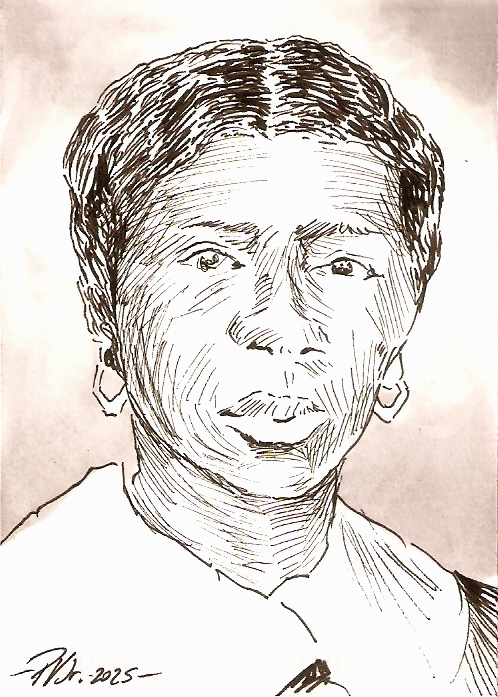

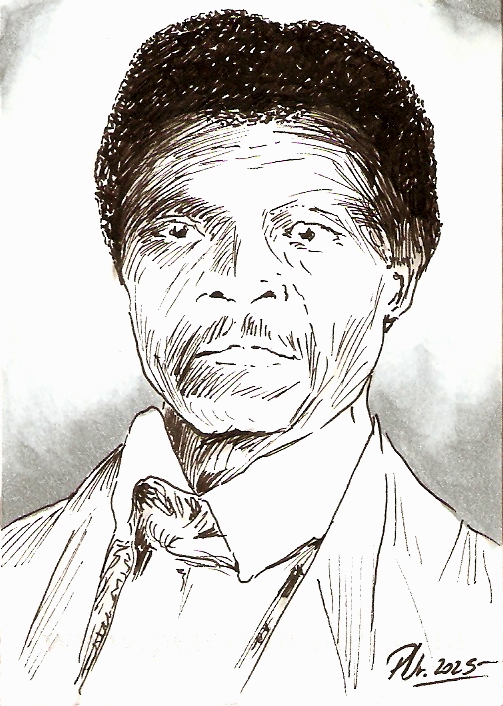

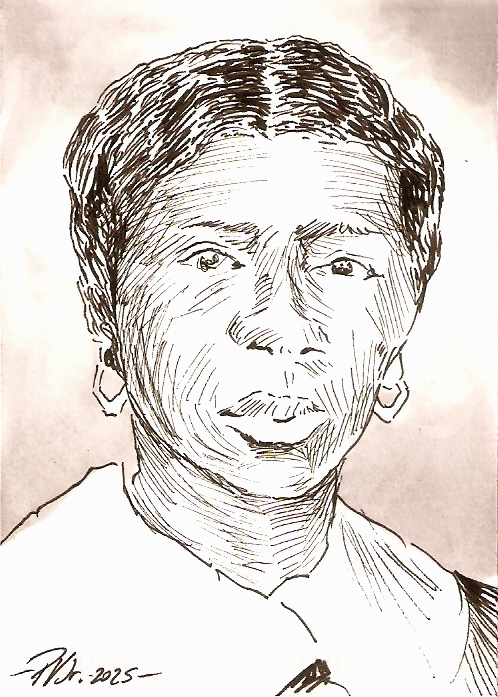

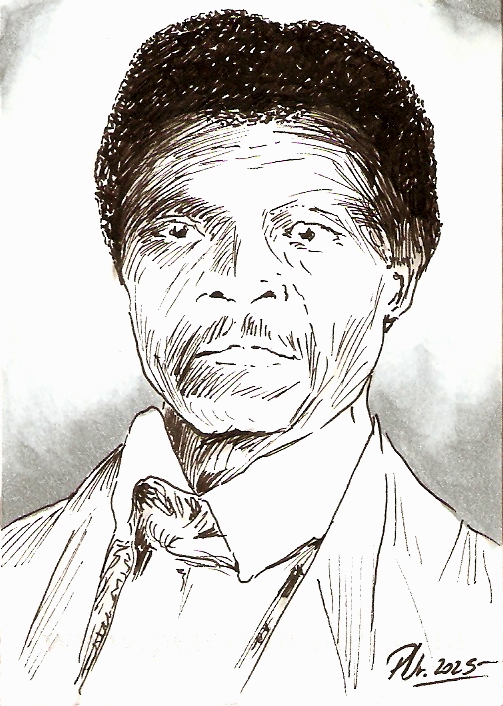

Dred Scott and Harriet Robinson Scott

An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted on 09/15/2025

It appears that we're talking about slavery far too much, and that the mere mention of the subject is upsetting some people. Which is of course our cue to immediately launch into a detailed study of the lives of Dred Scott and his wife Harriet Robinson Scott; who together found themselves at the very core of the Supreme Court's shameful Dred Scott v. Sandford decision of 1857. Since today's U.S. Supreme Court is of course far more enlightened and progressive on the issues of civil rights and birthright citizenship, I imagine a deep dive into this landmark case's background would be nothing more than a harmless academic legal curiosity --certainly nothing against which any current events might be measured or cautioned.

Born enslaved in Southampton, Virginia, thought to be in the year 1795, Dred was the property of one Peter Blow, who at one point moved his family and all of his slaves to Huntsville, Alabama. In 1831 Blow died and Dred was sold to one John Emerson, a U.S. Army surgeon. In 1836 Emerson was transferred to Fort Snelling in what was then known as the Northwest Territories (later Minnesota), where slavery was outlawed. However this regulation was often quietly overlooked where the military was concerned, and Dr. Emerson's case was no exception, even though Dred also travelled with him to reside in other free states like Illinois and Wisconsin.

Born enslaved in Southampton, Virginia, thought to be in the year 1795, Dred was the property of one Peter Blow, who at one point moved his family and all of his slaves to Huntsville, Alabama. In 1831 Blow died and Dred was sold to one John Emerson, a U.S. Army surgeon. In 1836 Emerson was transferred to Fort Snelling in what was then known as the Northwest Territories (later Minnesota), where slavery was outlawed. However this regulation was often quietly overlooked where the military was concerned, and Dr. Emerson's case was no exception, even though Dred also travelled with him to reside in other free states like Illinois and Wisconsin.

Harriet was likewise born enslaved in Virginia, thought to be in the year 1815 --though some accounts place her birth as late as 1820. Her enslaver, Lawrence Taliaferro, was also a military officer who was reassigned as an Indian agent in 1830, and brought Harriet along to Fort Snelling, again quietly sidestepping the ostensible ban on slavery in the Northwest Territories. Significantly, Taliaferro married Harriet and Dred in a civil ceremony in 1836, and the Scotts raised two daughters; all were then considered to be employed by the Emersons (even periodically being hired out to other employers), but were otherwise living as free people.

Harriet was likewise born enslaved in Virginia, thought to be in the year 1815 --though some accounts place her birth as late as 1820. Her enslaver, Lawrence Taliaferro, was also a military officer who was reassigned as an Indian agent in 1830, and brought Harriet along to Fort Snelling, again quietly sidestepping the ostensible ban on slavery in the Northwest Territories. Significantly, Taliaferro married Harriet and Dred in a civil ceremony in 1836, and the Scotts raised two daughters; all were then considered to be employed by the Emersons (even periodically being hired out to other employers), but were otherwise living as free people.

After Dr. Emerson died in 1843, ownership of the Scotts passed to his wife Irene, and they all moved to St. Louis; in other words, back to a slaveowning state (as enumerated under the terms of the still-new Missouri Compromise, only codified into law just a few years earlier). It is assumed by most historical accounts that Dred then attempted to buy his family's freedom, but Irene refused. This led to the Scotts filing a suit for their freedom in St. Louis Circuit Court, in 1846, the beginning of a tumultuous legal path that would take years and ultimately lead to what is almost universally agreed to be the worst-ever decision in the entire history of SCOTUS. *

An oft-overlooked detail is the fact that, at first, the Scotts initially did successfully win their freedom in 1850 --in truth it was a pretty airtight case, based on established Missouri law and precedent; that an enslaved person, once relocated to a free state or territory, could not be re-enslaved. Unfortunately it was Irene's appeal that accelerated the trouble: the Missouri state supreme court overruled the local court's decision with little more than a dismissive "Times now are not as they were." Undeterred, the Scotts pushed on and filed suit in Federal court (with assistance from local abolitionists). By this point Irene had left St. Louis and remarried, and the merits of the case were now (somehow) being argued by her brother, John Sandford.

Setting aside the horrifying --nay, seismic-- ramifications of the Supreme Court's 7-2 decision; and Roger Taney's callous observation that Scott never had any legal standing to sue because Black people "are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution;" to say nothing of the larger role this ruling would play in upending the Northwest Ordinance and the Missouri Compromise, permanently demoting Black Americans to nonvoting underclass status, and indeed speedrunning the start of the Civil War; there was still a happy ending (of sorts) at the tail end of the Scotts' own personal journey. Their St. Louis owner, Congressman Taylor Blow (the son of Dred's original owner), freed the Scotts in 1857. While Dred himself died only a year later, Harriet lived until the age of 61 in St. Louis as a free woman, earning her own money and enjoying the company of her free-born grandchildren. The Scotts are buried in Greenwood Cemetery, one of the first Black burial grounds in St. Louis.

* - Yeah. Give it time...

Next lesson - Lesson 202: Abraham Galloway

Return to www.petervintonjr.com Main Page

Born enslaved in Southampton, Virginia, thought to be in the year 1795, Dred was the property of one Peter Blow, who at one point moved his family and all of his slaves to Huntsville, Alabama. In 1831 Blow died and Dred was sold to one John Emerson, a U.S. Army surgeon. In 1836 Emerson was transferred to Fort Snelling in what was then known as the Northwest Territories (later Minnesota), where slavery was outlawed. However this regulation was often quietly overlooked where the military was concerned, and Dr. Emerson's case was no exception, even though Dred also travelled with him to reside in other free states like Illinois and Wisconsin.

Born enslaved in Southampton, Virginia, thought to be in the year 1795, Dred was the property of one Peter Blow, who at one point moved his family and all of his slaves to Huntsville, Alabama. In 1831 Blow died and Dred was sold to one John Emerson, a U.S. Army surgeon. In 1836 Emerson was transferred to Fort Snelling in what was then known as the Northwest Territories (later Minnesota), where slavery was outlawed. However this regulation was often quietly overlooked where the military was concerned, and Dr. Emerson's case was no exception, even though Dred also travelled with him to reside in other free states like Illinois and Wisconsin.