An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted 2/7/2023

Prelude | 109 | 110 | 111 | 112 | 113 | 114 | 115 | 116 | 117 | Email |

|---|

"The trigger for white rage, inevitably, is Black advancement. It is not the mere presence of Black people that is the problem; rather, it is Blackness with ambition, with drive, with purpose, with aspirations, and with demands for full and equal citizenship."

--Carol Anderson, from her 2016 book White Rage

Long one today. And it is not going to be an easy read, so decide now.

In the weeks leading up to the November 2, 1920 elections, the small unincorporated Florida town of Ocoee, just northwest of Orlando, saw an alarming uptick in parades of white supremacists' marches and rallies, vowing that no Black citizen would be permitted to vote. Sure enough, on November 2 many determined Black citizens did indeed turn up at polling places and were barred from entering on one flimsy Jim Crow pretext or another; and in many instances where they did enter, found their names "mysteriously" absent from registration rolls. Not everyone was so easily dissuaded, and a lawsuit was filed against the County that very day by one Mose Norman, a well-to-do orange grove owner. Norman returned from Orlando later that afternoon after having met with Judge John M. Cheney, an aspiring Senate candidate who was himself a strong advocate for Black voter registration. Judge Cheney instructed Norman to return to Ocoee and collect the names of every Black citizen who had not been permitted to vote and to also record the names of each and every poll worker who had denied them. Mose Norman did so and defiantly decreed, "We will vote, by God!"

The response from the Ku Klux Klan and their Dixiecrat apologists/fanboys was predictable and immediate: over the next two days more than 25 homes, the masonic lodge, a school, and the African Methodist Episcopal Church would be burned to the ground --some with people still inside. In total an estimated 56 Black people would be brutally murdered, and an entire Black population essentially purged, not only from the town itself but very nearly from historical memory.

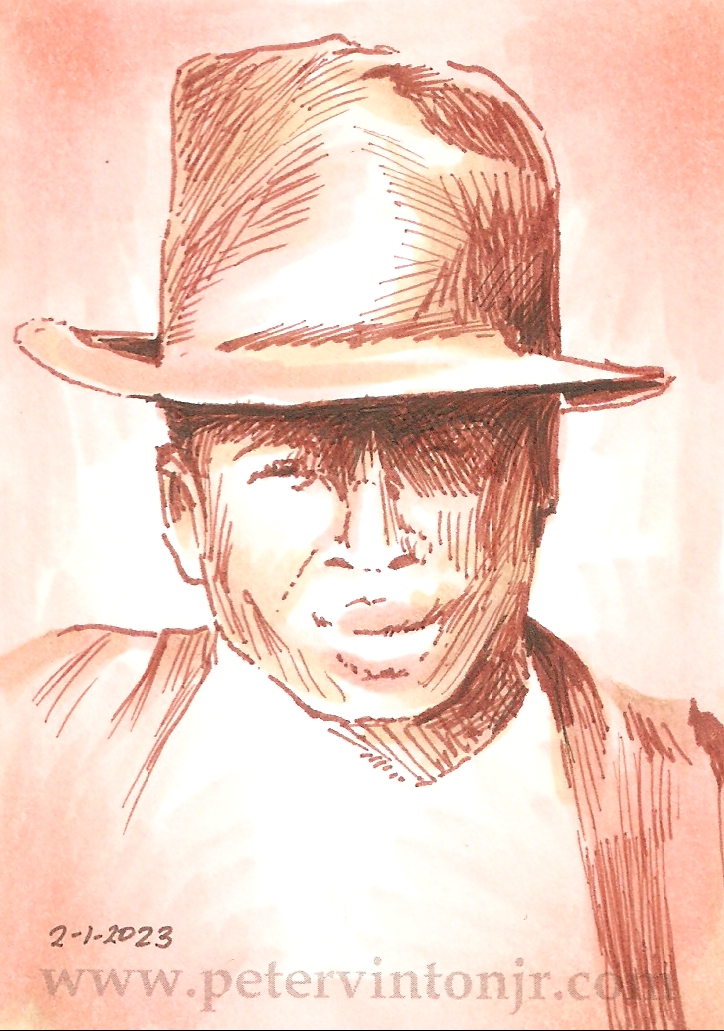

One of the first people to be murdered by the mob was Julius "July" Perry, a longtime friend of Norman; another well-to-do farm owner, and a respected local labor leader and church deacon, known for aggressively speaking out on behalf of Blacks to be educated, and to stand up for themselves as full and first-class citizens. In an essay Ocoee On Fire by Jason Byrne, Perry is described as a "civil rights leader before there was a civil rights movement." Having been identified by an angry white mob as an "instigator," Norman Mose had fled to Perry's home but unfortunately the mob soon twigged to Mose's whereabouts and surrounded Perry's home. The ringleader, a former Orlando police officer named Sam Salisbury, was the first to force his way into the house. Unfortunately the specifics of the confrontation are widely conflicting, which of course muddies an honest reckoning of events even decades later. Perry's wife and children, also cornered in the house, defended themselves --in particular his daughter Coretha swung a rifle into Salisbury's stomach, which (apocryphally) then fired and prompted hails of bullets from both inside and outside the house. Two of the mob were killed as they tried to force their way into the back door, and July and Coretha were both wounded, but in the confusion Perry's family managed to escape. By then the word had gone out and additional Klan had descended on the small town in more than 50 cars, having arrived from surrounding counties and towns. The so-called "local militia," curiously populated by more outsiders than actual locals, organized a manhunt and Perry was soon arrested. Later that evening a lynch mob descended on the county jail where Perry was being held, and local sheriff Frank Gordon promptly handed over the keys to his cell.

The following morning Perry's beaten and bullet-ridden body, having allegedly been dragged through the streets by vigilantes, was found hanging from a telephone pole near the entrance to the Orlando Country Club --in easy view from the front of Judge Cheney's home. The message was clear. Perry's body was quietly interred in an unmarked grave until 2002, when a local movement finally deduced his remains' location and at last moved him to a memorial grave at Greenwood Cemetery in Orlando.

In the meantime, well beyond the horrors visited upon Perry, the mob had run wild --between November 2 and November 4 hundreds of Black people and families would flee into the swamps and groves to escape; more fearful of the KKK than of wildcats or alligators. The abandonment was instant and total: almost none would ever again return to the town, including Mose Norman, who eventually settled in Harlem; and Coretha Perry, who, despite her lifelong bullet wound, would never again speak the word "Ocoee" or even look at it on a map. According to census records the town had not one single Black citizen until 1978, and even as recently as the 1990s there was a prevailing folk wisdom that Black people shouldn't linger outside after dark. This long silence was eerily mirrored in the press's accounts of events --differing versions of details, denials and outright cover-ups emerged to obscure the history until the event itself was essentially absent; with far greater emphasis placed on the deaths of the two white men killed at Perry's home, but with little mention of the dozens of Black people killed or driven out; and even then only being reported in acceptably sanitized terms like "race riots" and "local disputes," and an unforgivably under-recorded death toll of eight, with generous helpings of "both-sides-ism" in the verbiage. Author Zora Neale Hurston (see Lesson #25 in this series) herself researched and wrote a short story about the Ocoee Massacre in 1939 but it did not find a receptive publisher, and lay undiscovered until 1989.

In a weirdly uncharacteristic (and frankly suspicious) reversal of the present-day imperative that is currently being pushed by Florida education officials, a law was signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis requiring that the Ocoee Election Day Massacre be taught in Florida schools. (UPDATE 9/3/2023 - Yeah, I should have known there'd be strings attached. Way to victim-blame, there, Ron.) A section of State Route 438 has been renamed July Perry Highway, and historic markers have been placed and dedicated. Perhaps the most significant landmark, though, is Perry's gravesite itself --traditionally after every election, scores of voters drop by to affix their "I Voted" stickers to the headstone.

View The Truth Laid Bare, a 12-minute video produced by the University of Central Florida, about the Ocoee Massacre

Further recommended reading: Visions Through My Father's Eyes, a memoir by Gladys Franks Bell (a great-niece of Perry), recounting her own family's flight from Ocoee the night of November 2, 1920.

Next page - Lesson 114: Anna Louise James