An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted 2/15/2023

Prelude | 111 | 112 | 113 | 114 | 115 | 116 | 117 | 118 | 119 | Email |

|---|

"One of the problems in the United States is the refusal on the part of our young people to remember or to want to remember, or to recognize the experiences of the past as being relevant, germane, important to the present and to the future. They simply don't want anything that's painful. They want to live in a painless society where everything is pleasant, and everything is joyful."

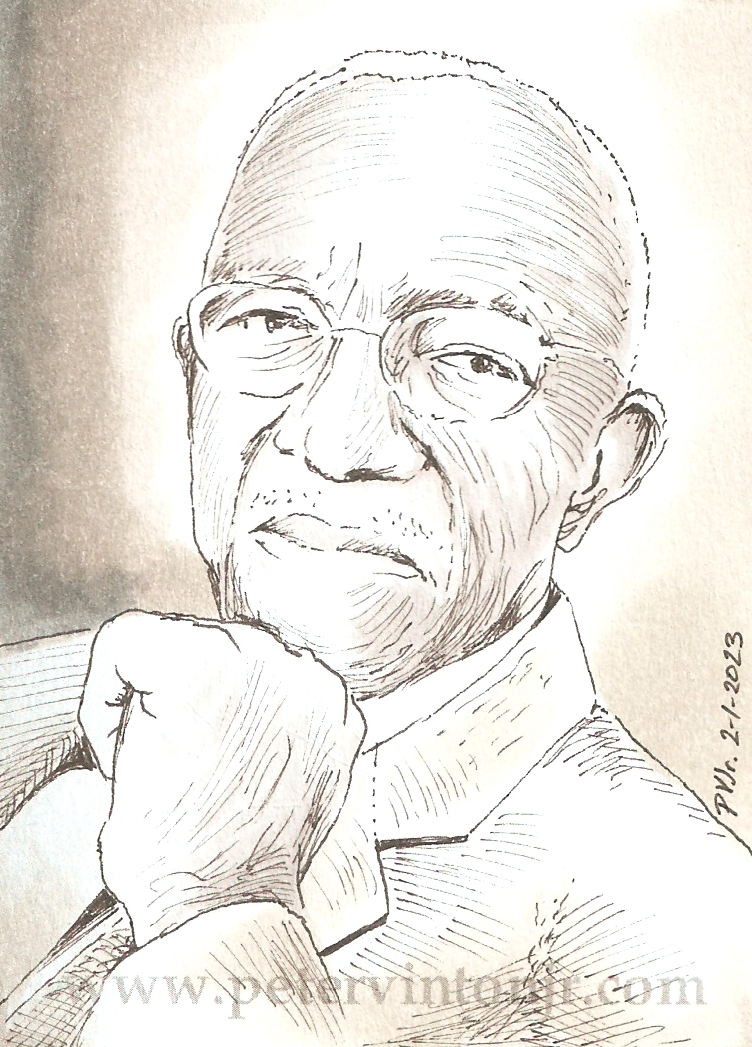

The quiet but unrelenting legacy of historian John Hope Franklin might be said to have been foreshadowed years before his birth in Tulsa 1915; the son of Buck Colbert Franklin, himself a successful attorney and an eyewitness to the events of the Tulsa Race Massacre and its aftermath. John, himself named for John Hope, the first Black president of Clark Atlanta University, would later graduate from Fisk University in 1935, and then earn advanced degrees in history at Harvard --an M.A. in 1936 and then a Ph.D in 1941.

It would not be an easy path: as a child in Tulsa he rushed to help a blind white woman cross the street until she realized he was black and ordered him to take his "filthy hands off her." As a student at Fisk, he tells the story of having handed a $20 dollar bill to a streetcar employee and asking for change, inviting a racial slur. During World War II Franklin taught at both St. Augustine's College and at the North Carolina College for Negroes (today known as North Carolina Central University). Later in 1953 he worked with then-judge Thurgood Marshall and other NAACP lawyers on developing some of the legal arguments for what would become the Brown v. Board Of Education decision --during preparations, for a time he worked at the state archives in Raleigh, NC, where he was restricted to a small anteroom across from the "whites-only" research room. Franklin also participated with other fellow historians and academics in the march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.

Over the course of his career Franklin published many books and historical studies, to include The free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-1860 (1943); and The militant South, 1800-1861 (1956), but Franklin's greatest accomplishment comes in the form of his 1947 publication of From Slavery to Freedom: a history of American Negroes, which first appeared during his tenure at Howard University (1947-1956). To this day the book remains a seminal text on African-American studies throughout the United States, now into its Ninth Edition and having sold upwards of 3.5 million copies. Fellow historian Henry Louis Gates Jr., cites the book as the definitive work on race relations in America, and named Franklin as his intellectual godfather and "the prince of black academics."

Following his time at Howard University, in 1956 Franklin became chairman of the Department of History at Brooklyn College --the first Black person to do so. In 1967 he then became a professor of American History at the University of Chicago; and in 1982 he returned to North Carolina, this time to teach at Duke University as Professor Of Legal History. In 1997 President Clinton appointed Franklin to lead One America, a national initiative on race.

"I hardly needed to seek a way to confront American racial injustice. My ambition was sufficient to guarantee that confrontation."

Franklin died at his beloved Duke (Duke Hospital) the morning March 25, 2009, having lived long enough to see a Black man elected to the U.S. Presidency. In 2010 the City of Tulsa renamed Reconciliation Park, established to commemorate the victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, as John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park.

Next page - Lesson 116: Dangerfield Newby