An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted 3/24/2023

Prelude | 118 | 119 | 120 | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 125 | 126 | Email |

|---|

"O woman, woman, upon you I call. For upon your exertions almost entirely depends on whether the rising generation shall be anything more than what we have been or not. O woman, woman, your example is powerful, your influence great, it extends over your husbands and your children, and throughout the circle of your acquaintance."

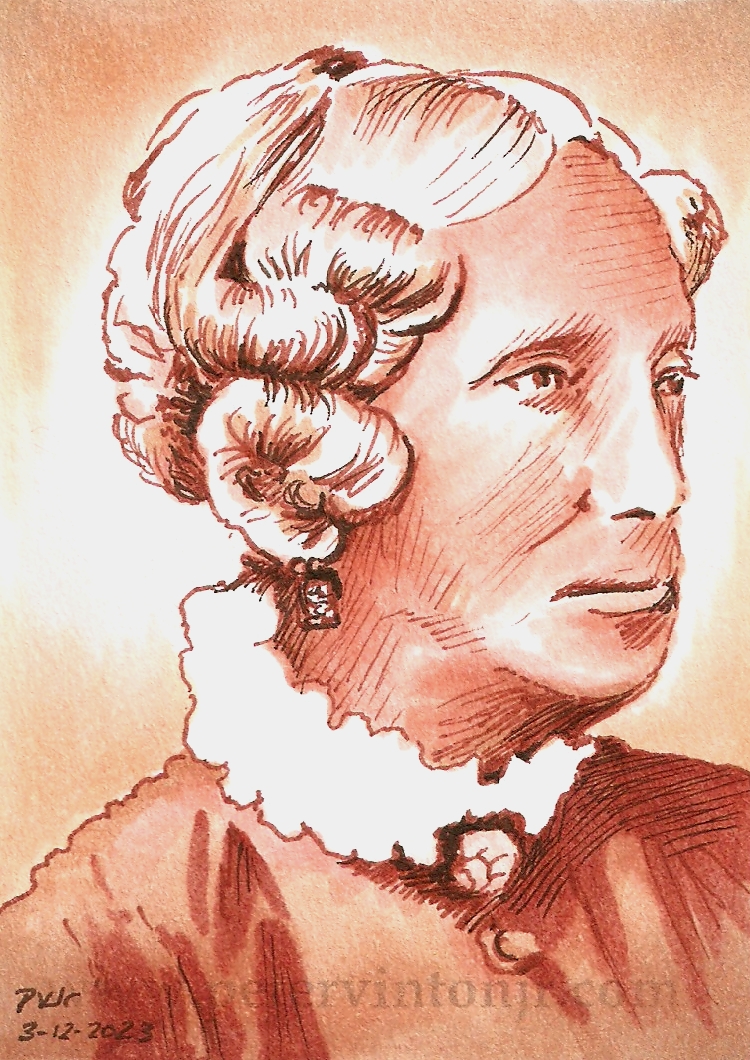

Meet outspoken writer, orator and intellectual Maria Stewart. Born to free to African-born parents in 1803 Connecticut, Maria was sadly orphaned at the age of 5, and was then "bound out" as an indentured servant (we all know what that means, but: nice try, recently-revised Florida public school curricula!) the family of a local clergyman. At the age of 15 she moved to Boston and married local businessman (and War Of 1812 veteran) James W. Stewart, and settled into the Beacon Hill neighborhood --at the time a thriving and unusually progressive middle-class Black community. The Stewarts cultivated the friendship of local abolitionist and activist David Walker (a name that will very likely soon merit its own entry in this series). Walker was particularly known for taking Christianity to task (or more scathingly in his words, pretenders to Christianity) whenever they made excuses for --or outright defended-- slavery. Walker accused so-called Christians of hypocritically twisting their own faith's basic precepts to justify treating Black people even more barbarously and cruelly than any other faith. This made a vivid impression on Maria, herself a devout Christian.

Sadly Maria's life took a few more unpleasant turns --in short order her husband James and their dear friend David Walker both died. Denied an inheritance by the executors of James's own will, she had to resort to returning to a life of domestic servitude. However Maria's own religious faith remained unshakeable and she began writing antislavery articles in much the same vein as Walker's essays --eventually attracting the notice of noted abolitionist (and influential editor!) William Lloyd Garrison in 1831. Maria's essays appeared regularly in The Liberator, Garrison's antislavery newspaper.

Amongst Maria's essays, perhaps her most foundation-shaking work was a full-length pamphlet titled "Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, The Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build." In this essay Maria pointedly spoke to the notion of freedom for all Black women regardless of status, and called upon Black women to uplift one another. But perhaps even more effectively, Maria invoked Christian rhetoric and principles to make her case --that the teachings of Jesus Christ ran absolutely counter to the notion that slavery should in any way be condoned or upheld, or even (as some arguments went) that Black people somehow deserved their enslavement. (Yes, victim-blaming isn't exactly a new practice, folks.) Unsurprisingly Maria deftly cited many chapters and verses to help make her case. The pamphlet, however, also left some room to criticize Black individuals themselves --suggesting that they were not, in fact, actively doing enough to secure greater freedom for themselves; an admonition to "take the plank out of our own eye," that met with some pushback.

Maria also intrinsically understood --perhaps more so than most-- that America's prosperity was directly dependent upon Black servitude and brutality; that slavery was encoded into America's very economic framework and that it would be a phenomenally difficult job to extricate it. Maria's success as a writer led in turn to more and more speaking engagements. One particular group that invited her to speak, was known as The Afric-American Female Intelligence Society Of Boston (yes, that really is the full name!), and significantly Maria's February 27, 1833 speech was addressed to a large crowd of Black and white people, comprised of both men and women. It's important to understand how, in context, just how groundbreaking such an audience truly was, in the 1830s. Maria continued to travel and teach (and evangelize!) over the years, delivering speeches in New York, Baltimore, and eventually Washington, D.C., where she ultimately settled and became Head Matron of the Freedman's Hospital and Asylum (later the medical school of Howard University). Contemporaneously her published writings found their way into many libraries and schools --a rarity in a time when so many Black people in America were still subjugated.

Next page - Lesson 123: Oney Judge