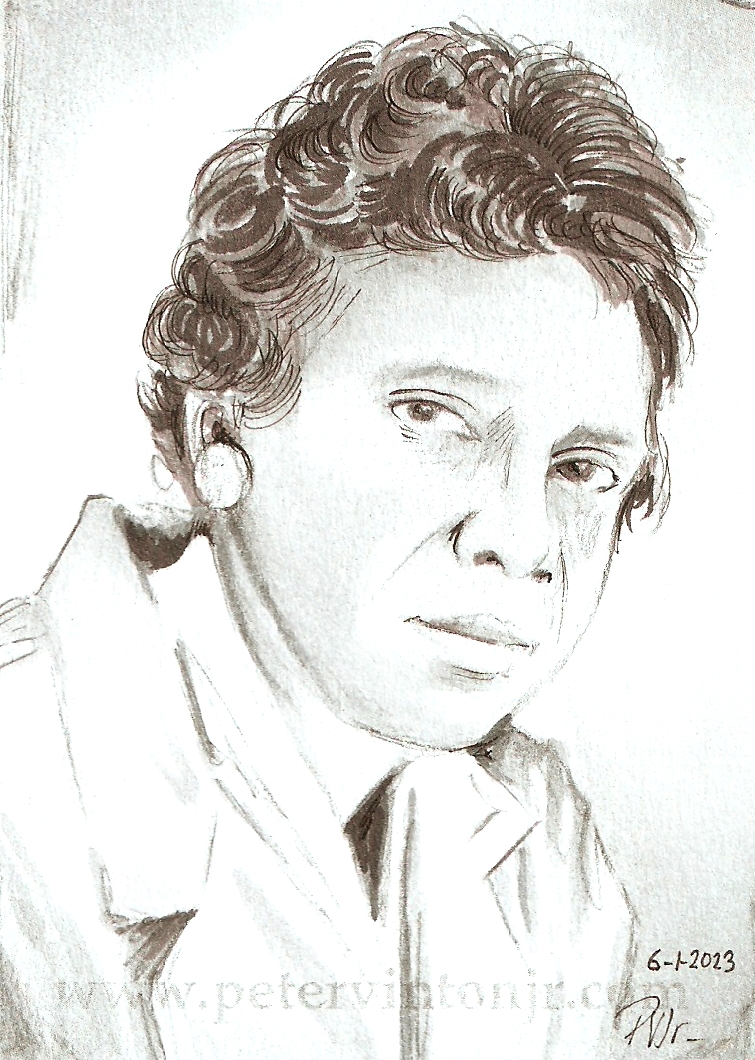

Lesson 126:

Barbara Jordan

An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted 6/1/2023

"We, the people. It's a very eloquent beginning. But when that document was completed on the seventeenth of September in 1787, I was not included in that 'We, the people.' I felt somehow for many years that George Washington and Alexander Hamilton just left me out by mistake. But through the process of amendment, interpretation, and court decision, I have finally been included in We, the people. Today I am an inquisitor. An hyperbole would not be fictional and would not overstate the solemnness that I feel right now. My faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total. And I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction, of the Constitution."

--from Barbara Jordan's opening remarks to the House Judiciary Committee on July 24, 1974, regarding the impeachment of Richard Nixon

Today, June 1, kicks off Pride Month (and also incidentally marks the third anniversary of the start of this series), and I thought it appropriate to examine the amazing accomplishments of Texas civil rights leader, attorney, and Congresswoman Barbara Charline Jordan.

Born in a poor Houston neighborhood in 1936, Jordan discovered an early aptitude for languages and oration, and also debate. She graduated from Texas Southern University in 1956, then obtained her LL.B. from Boston University School of Law in 1959. She was admitted to both the Massachusetts and Texas bars in 1960, then began practicing law in Houston --at the time only the third African American woman to be so licensed. An outspoken supporter of John F. Kennedy's presidential campaign, she herself entered politics and unsuccessfully ran for state representative in 1962 and again in 1964. Two years later her fortunes changed, however, and in 1966 she became the first African American elected to the Texas Senate in 1966.

Born in a poor Houston neighborhood in 1936, Jordan discovered an early aptitude for languages and oration, and also debate. She graduated from Texas Southern University in 1956, then obtained her LL.B. from Boston University School of Law in 1959. She was admitted to both the Massachusetts and Texas bars in 1960, then began practicing law in Houston --at the time only the third African American woman to be so licensed. An outspoken supporter of John F. Kennedy's presidential campaign, she herself entered politics and unsuccessfully ran for state representative in 1962 and again in 1964. Two years later her fortunes changed, however, and in 1966 she became the first African American elected to the Texas Senate in 1966.

Jordan's standing as a fellow Texan Democrat endeared her to then-President Lyndon Johnson and in many respects she became LBJ's protégée. In 1972 Jordan ran for Congress for Texas's 18th District, and unseated the incumbent Republican, becoming the first woman --of any race-- elected to Congress from that state.

Jordan's political career accomplishments extend far beyond this biography's available space, but among the high points include her aggressive sponsorship of the Voting Rights Act of 1975 (an extension of the more famous 1965 measure), and the Equal Rights Amendment in 1977. Also significantly she served on the House Judiciary Committee during the Nixon impeachment hearings, and her speech at the 1976 Democratic National Convention is widely regarded as one of the best keynote speeches in modern history; her presence in many ways even eclipsing that of the party's nominee, Jimmy Carter. (She would return as a keynote speaker for the 1992 Democratic National Convention.)

Jordan retired from politics in 1978 and became a professor at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas in Austin. In 1993 Jordan was the first recipient of the Nelson Mandela Award for Health and Human Rights. A year later she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Bill Clinton for her trailblazing work. That same year Jordan was also named the chair of the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform. Jordan died from complications from pneumonia in January of 1996, and is buried at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin --significantly breaking barriers even in death as the first-ever black woman to be interred there. While Jordan never explicitly acknowledged her personal sexual orientation in public, she was open about her life partner of nearly 30 years, educational psychologist Nancy Earl.

Her legacy continues through the Jordan Rustin Coalition (named for her and for Civil Rights organizer Bayard Rustin --see Lesson #05 in this series): a non-profit advocacy group working to empower Black same-gender loving, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals and families; and to promote equal marriage rights and to advocate for fair treatment of everyone without regard to race, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression.

Full text of Jordan's July 24, 1974 remarks: https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/impeachment/my-faith-constitution-whole-it-complete-it-total

A truly absorbing 1976 article about Jordan's life and career by William Broyles, indexed at: https://www.texasmonthly.com/news-politics/the-making-of-barbara-jordan-2/

Next page - Lesson 127: Stormé DeLarverie

Return to www.petervintonjr.com Main Page

Born in a poor Houston neighborhood in 1936, Jordan discovered an early aptitude for languages and oration, and also debate. She graduated from Texas Southern University in 1956, then obtained her LL.B. from Boston University School of Law in 1959. She was admitted to both the Massachusetts and Texas bars in 1960, then began practicing law in Houston --at the time only the third African American woman to be so licensed. An outspoken supporter of John F. Kennedy's presidential campaign, she herself entered politics and unsuccessfully ran for state representative in 1962 and again in 1964. Two years later her fortunes changed, however, and in 1966 she became the first African American elected to the Texas Senate in 1966.

Born in a poor Houston neighborhood in 1936, Jordan discovered an early aptitude for languages and oration, and also debate. She graduated from Texas Southern University in 1956, then obtained her LL.B. from Boston University School of Law in 1959. She was admitted to both the Massachusetts and Texas bars in 1960, then began practicing law in Houston --at the time only the third African American woman to be so licensed. An outspoken supporter of John F. Kennedy's presidential campaign, she herself entered politics and unsuccessfully ran for state representative in 1962 and again in 1964. Two years later her fortunes changed, however, and in 1966 she became the first African American elected to the Texas Senate in 1966.