Lesson 209:

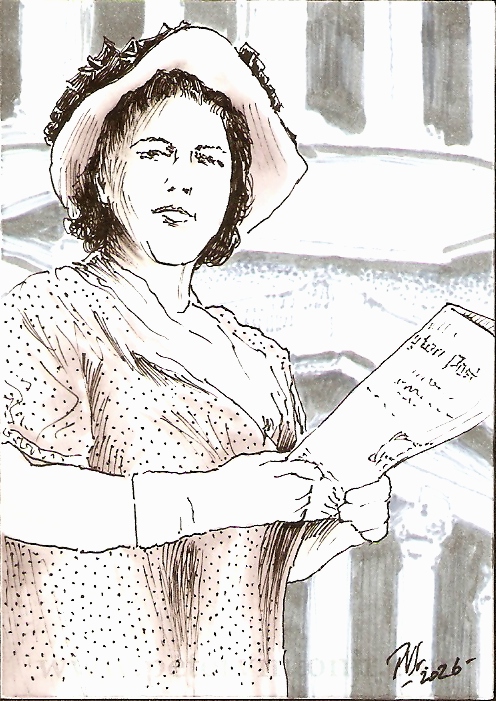

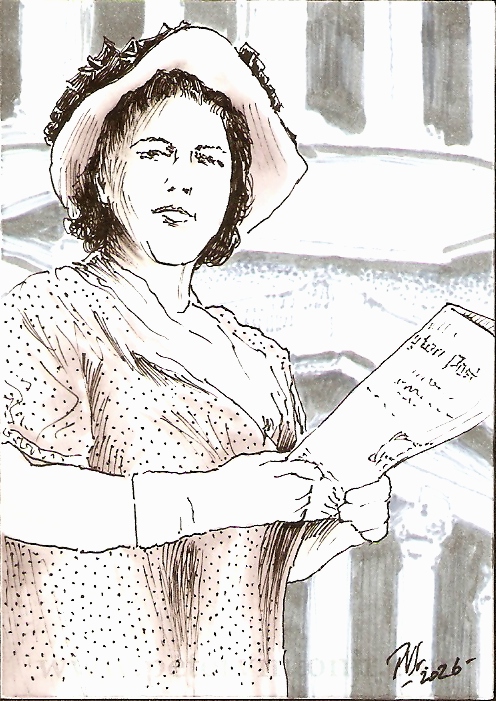

Alice Dunnigan

An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted on 02/01/2026,

Black History Month 2026

"Race and sex were twin strikes against me."

We set to work upon Black History Month 2026, with a continued focus on journalism. Born 1906 and brought up in heavily-segregated Kentucky, Alice Allison Dunnigan pushed back against the limited (and degrading) job opportunities of Jim Crow South and pursued her dream of being a reporter. As early as age thirteen, she was writing editorials for the Louisville Defender, the Louisville Leader, and the Derbytown Informer, and ultimately graduated from Tennessee A&I University with a degree in journalism. During World War II she worked in Washington, D.C. for the Department of Labor, and in the postwar years became the Washington Bureau Chief for the American Negro Press (ANP), which provided stories to newspapers around the world.

We set to work upon Black History Month 2026, with a continued focus on journalism. Born 1906 and brought up in heavily-segregated Kentucky, Alice Allison Dunnigan pushed back against the limited (and degrading) job opportunities of Jim Crow South and pursued her dream of being a reporter. As early as age thirteen, she was writing editorials for the Louisville Defender, the Louisville Leader, and the Derbytown Informer, and ultimately graduated from Tennessee A&I University with a degree in journalism. During World War II she worked in Washington, D.C. for the Department of Labor, and in the postwar years became the Washington Bureau Chief for the American Negro Press (ANP), which provided stories to newspapers around the world.

Predictably Dunnigan started out earning half the pay of the men she worked with, though over time she successfully argued for the same regular salary. Neither the ANP nor its competitor, the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) were at the time able to access the highly-coveted Capitol Press Galleries. To say the situation was difficult for a Black woman in Washington, D.C. in those years is a grievous understatement. She covered civil rights cases, segregation, and federal fair employment legislation --often paying out of her own pocket to be able to get exclusive stories. Then in 1947 fortunes changed and Dunnigan found herself the first Black woman to cover the White House, the Supreme Court and Congress (the first Black man to break that barrier was her colleague Harry McAlpin just three years earlier... more about him in the very next lesson).

She rose to the opportunity: in 1948, she was the only Black reporter assigned to Harry S. Truman's famous Whistle Stop campaign train: she conducted in-depth interviews with service workers aboard the "rolling White House" train for behind-the-scenes pieces, and even ran a special feature on the president's valet. President Eisenhower famously bristled at --and evaded-- her tough questions about racial discrimination in federal departments; this particular "offense" carried a professional consequence, as she found herself yanked (at the last minute) from the team that was to cover the funeral of Senator Robert Taft, that same week. (Sure is a good thing today's journalists aren't punished for that sort of behaviour, huh?) #hannahnatanson

As a civil rights journalist, Dunnigan's work for the ANP enriched the coverage of key issues at the dawn of the civil rights movement --issues of greater importance to Black Americans, like housing problems and employment issues, which might otherwise have gone unreported. Dunnigan left journalism as a career in the early 1960's, and returned to a full-time role with the Department of Labor, and also as an advisor on the President's Council on Youth Opportunity, and then later taking a consultant role in President Johnson's then-new Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. She retired in 1970 and her memoir, A Black Woman's Experience - From Schoolhouse to White House, was published in 1974.

Next lesson - Lesson 210: Harry McAlpin

Return to www.petervintonjr.com Main Page

We set to work upon Black History Month 2026, with a continued focus on journalism. Born 1906 and brought up in heavily-segregated Kentucky, Alice Allison Dunnigan pushed back against the limited (and degrading) job opportunities of Jim Crow South and pursued her dream of being a reporter. As early as age thirteen, she was writing editorials for the Louisville Defender, the Louisville Leader, and the Derbytown Informer, and ultimately graduated from Tennessee A&I University with a degree in journalism. During World War II she worked in Washington, D.C. for the Department of Labor, and in the postwar years became the Washington Bureau Chief for the American Negro Press (ANP), which provided stories to newspapers around the world.

We set to work upon Black History Month 2026, with a continued focus on journalism. Born 1906 and brought up in heavily-segregated Kentucky, Alice Allison Dunnigan pushed back against the limited (and degrading) job opportunities of Jim Crow South and pursued her dream of being a reporter. As early as age thirteen, she was writing editorials for the Louisville Defender, the Louisville Leader, and the Derbytown Informer, and ultimately graduated from Tennessee A&I University with a degree in journalism. During World War II she worked in Washington, D.C. for the Department of Labor, and in the postwar years became the Washington Bureau Chief for the American Negro Press (ANP), which provided stories to newspapers around the world.